Moving from passive learning to active exploration of the physical world

October 29, 2018

This post is republished from Into Practice, a biweekly communication of Harvard’s Office of the Vice Provost for Advances in Learning

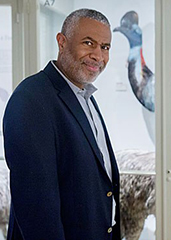

Scott Edwards, Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and Curator of Ornithology in the Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ), makes extensive use of the museum’s ornithology collections in his courses and brings specimens into his lecture sessions to engage students in close analysis during weekly three-hour labs. Edwards models “ways of making meaning” by looking to specimens as key evidence for testing claims and theories.

Scott Edwards, Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and Curator of Ornithology in the Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ), makes extensive use of the museum’s ornithology collections in his courses and brings specimens into his lecture sessions to engage students in close analysis during weekly three-hour labs. Edwards models “ways of making meaning” by looking to specimens as key evidence for testing claims and theories.

The benefits: Student engagement increases through the immediacy and level of detailed observation that comes from holding actual specimens. Edwards claims his students enjoy the “sheer coolness of knowing someone went out into the world and collected this” and uses that engagement to build students’ critical analysis skills, asking: “How do we evaluate a claim? How do we make inferences from evidence?”

The challenges: The astounding size and range of the MCZ collections (e.g., 400,000 ornithological specimens alone) can make it difficult to know where to start, and Edwards’ students are sometimes dubious that minute distinctions (such as slight differences in feather shape or color) really matter. Organizing the sometimes-overwhelming diversity into manageable packets and hierarchies of information can help ease stress that may arise.

Takeaways and best practices:

- Build the capacity to see. Edwards teaches through comparison, a “major method of figuring out what’s going on,” requiring students to draw specimens in the lab and immerse themselves in the details. Such a process allows students to explore a number of areas, including what a particular detail of a bird’s anatomy or plumage reveals not only about its behavior—but also evolution more broadly.

- Give students ownership. Edwards tasks students to present specific specimens to their classmates, speculating over why a skeleton is shaped the way it is, what the specimen “did for a living,” what it ate, and how it mated and socialized. Students then create names for the species, based on their own observations, often generating quite creative results.

- Build sequentially from foundational knowledge to patterns and to process. Edwards makes sure students have enough knowledge of fundamentals to name what they see and speculate on its meaning. Next steps involve identifying patterns in what they observe, and postulating on processes and parallels to other species or systems. Edwards replicates this sequencing in assignments and exams. For example, students receive a field guide from a country they have likely never visited, and are given two minutes to deduce the identity of a particular specimen from that guide—using their observations to offer connections and hypotheses.

Bottom line: Utilizing the rich resources of Harvard’s collections can enliven subject matter, raise crucial questions about the nature of evidence, and engage students in the process of critical thinking and reasoning in powerful ways. Direct use of collections strengthens students’ wonder and appreciation of the natural world: “If we can teach our students to love the earth, they’ll take care of it.”